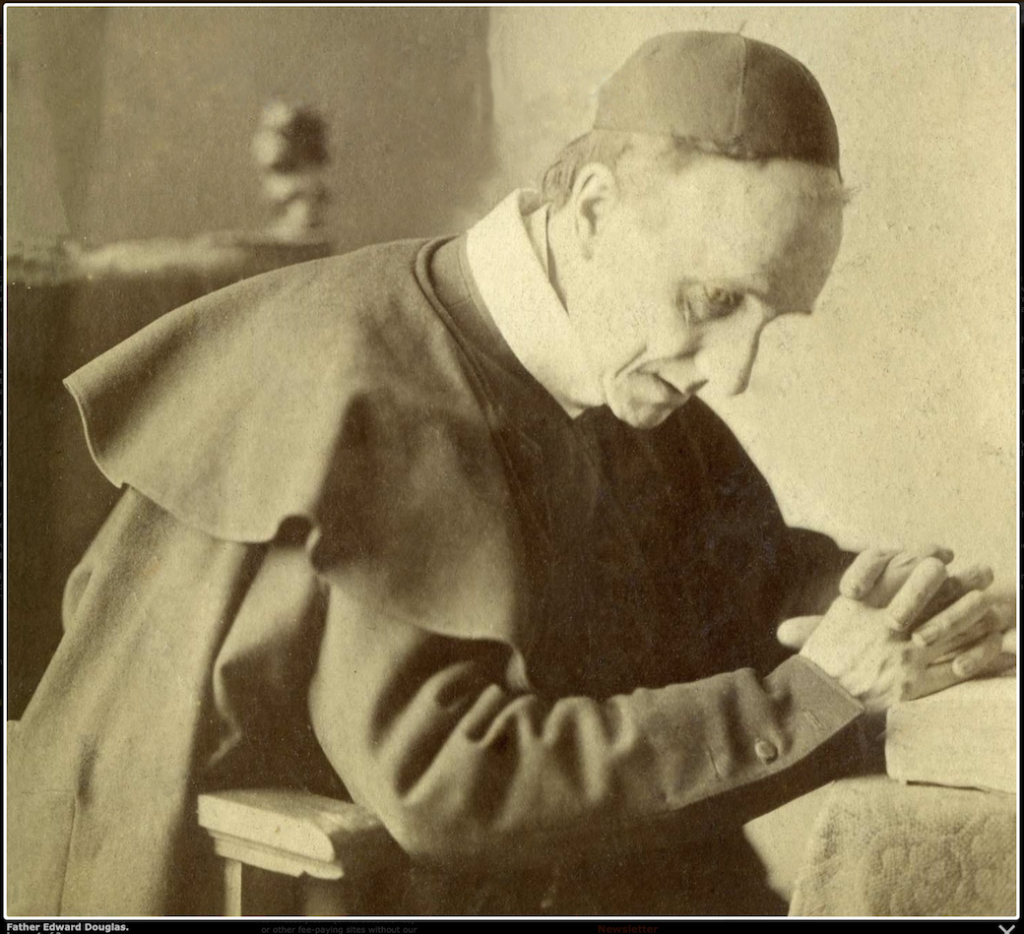

Reverend Edward Douglas was born on 1 December 1819. He was the son of Edward Bullock Douglas and Harriet Bullock. He died on 23 March 1898 at age 78. He was a Roman Catholic priest.

Edinburgh-born Edward Douglas, a wealthy Catholic convert, was kin to the Marquess of Queensberry, one of Scotland’s foremost families. A descendant of the Dukes of Queensbury and the Earls of Douglas and Mar, he was the sole heir to his family’s considerable wealth

Douglas had been brought up Protestant and the story of his conversion, as recorded in the “Tablet” newspaper archives, hinges on a chance incident involving a forgotten umbrella. The seeds had been sown while he was a student at Oxford. He was one of the so-called “Oxford Group” of students who were strongly influenced by the traditionalist theories of the theologist and philosopher John Henry Newman and who were subsequently to convert to Catholicism. Douglas’ own conversion, however, took place a few years later when he came to Rome. According to the story, he forgot his umbrella in a confessional in St. Peter’s where he was attended a papal ceremony and had to knock up the Carmelite brothers in order to retrieve it.

The actual conversation has not been recorded but it must have been extraordinarily illuminating, because he switched from the Anglican to the Roman faith and was subsequently ordained a priest, electing to join the Redemptorists, a missionary order founded near Amalfi by St.Alphonsus Maria dè Liguori a century earlier.

Fired with religious fervor and blessed with considerable organizational talents and plenty of disposable income, Father Douglas rose fast within the Order. In 1853 he got the task of setting up a General House in Rome. The Caetani palace, on what was then the quiet and leafy Esquiline hill, exactly suited his purpose and he purchased it with his own money for 45,000 scudi. He was to remain there as rector for the next forty years.

His first task was to build a church next to the General House, dedicated to the Redemptorists’ founder. The choice of architect fell on a fellow Scot (or maybe Irishman or Englishman) George Jonas Wigley, whose only other completed architectural work seems to be the modest St. Mary’s Woolhampton at Reading, Berkshire. Wigley, in fact, had a more distinguished career as a writer and journalist. He founded the Catholic newspaper, “The Universe” and was one of the founders of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, a volunteer organization under the wing of the Fathers Redeemers. Among the honours he received was a knighthood bestowed by Pope Pius IX.

Wigley designed the Redemptorist church in the preferred fashion of the Victorian age, which did not meet the taste of the Romans, accustomed to the classical and baroque. A noted critic of the period, in fact, said it was more “ostrogothic than gothic” and disparagingly dubbed it the “Troubador Style, in vogue in England”. The Fathers Redeemers, however, were convinced the church was blessed, because workers found a gold coin bearing an effigy of the Redeemer while digging the foundations.

Sant’Alfonso was also favoured by the benevolence of the Pope Pius IX, who decided to give it the 15th century sacred icon of Our Lady of Perpetual Succour, which was held to have miraculous powers. It was purchased (or stolen, stories vary) in Crete by an Italian merchant and brought to Rome.

On his deathbed, he instructed that it be carried to the Church of St. Matthew on Via Merulana so that it could be venerated by the faithful. During the procession, a paralytic girl regained the use of her legs and the sacred image became celebrated, attracting pilgrims from far and wide. One of the most assiduous of the devotees was the deposed Stuart monarch of Great Britain, James III or VIII, in exile in Rome.

When the French troops invaded, the monks from the neighbouring monastery hid the icon and it was forgotten for many years. When finally it finally came to light, the Pope thought it would be appropriate to return it to its original site, now occupied by the new Redemptorist church.

The icon is Byzantine in style, with brilliant colours on a gold background. However, the artist has introduced his own personal interpretation of the standard conventional image of the Virgin and Child. The baby clasps his mother’s thumb tightly between his little hands, as if seeking protection and reassurance, and, to add to the human touch, one of his sandals has fallen off and dangles from his foot.

The icon is revered in several countries, including Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and parts of Russia. The Madonna of Perpetual Succour is also the patron saint of Haiti, where she is known as “the Virgin of the Miracle” and was evoked (alas, not too successfully) by Pope Benedict XVI during the 2010 earthquake disaster.

The intervention of the miraculous icon was more successful during the Italian Risorgimento. In 1870, when Rome fell to Garibaldi’s troops, Father Douglas put up a valiant struggle to save Villa Caserta from confiscation. He declared it was his personal property and sent his title deeds to the British Ambassador, claiming diplomatic immunity. To reinforce his point, he hoisted the Union Jack from the roof. In the end, he was saved by the new King Victor Emmanuel of Savoy, who lent an ear to his pleas – perhaps with the help of a whisper from the Miraculous Virgin.

Fr. Douglas, a Scottish convert and descendant of the Dukes of Queensbury and the Earls of Douglas and Mar. The sole heir to the family’s considerable wealth, Fr. Douglas distributed it liberally on congregational projects, financing the 1854 purchase of the Roman property on Via Merulana and the subsequent construction of the headquarters and the adjacent St. Alphonsus church.

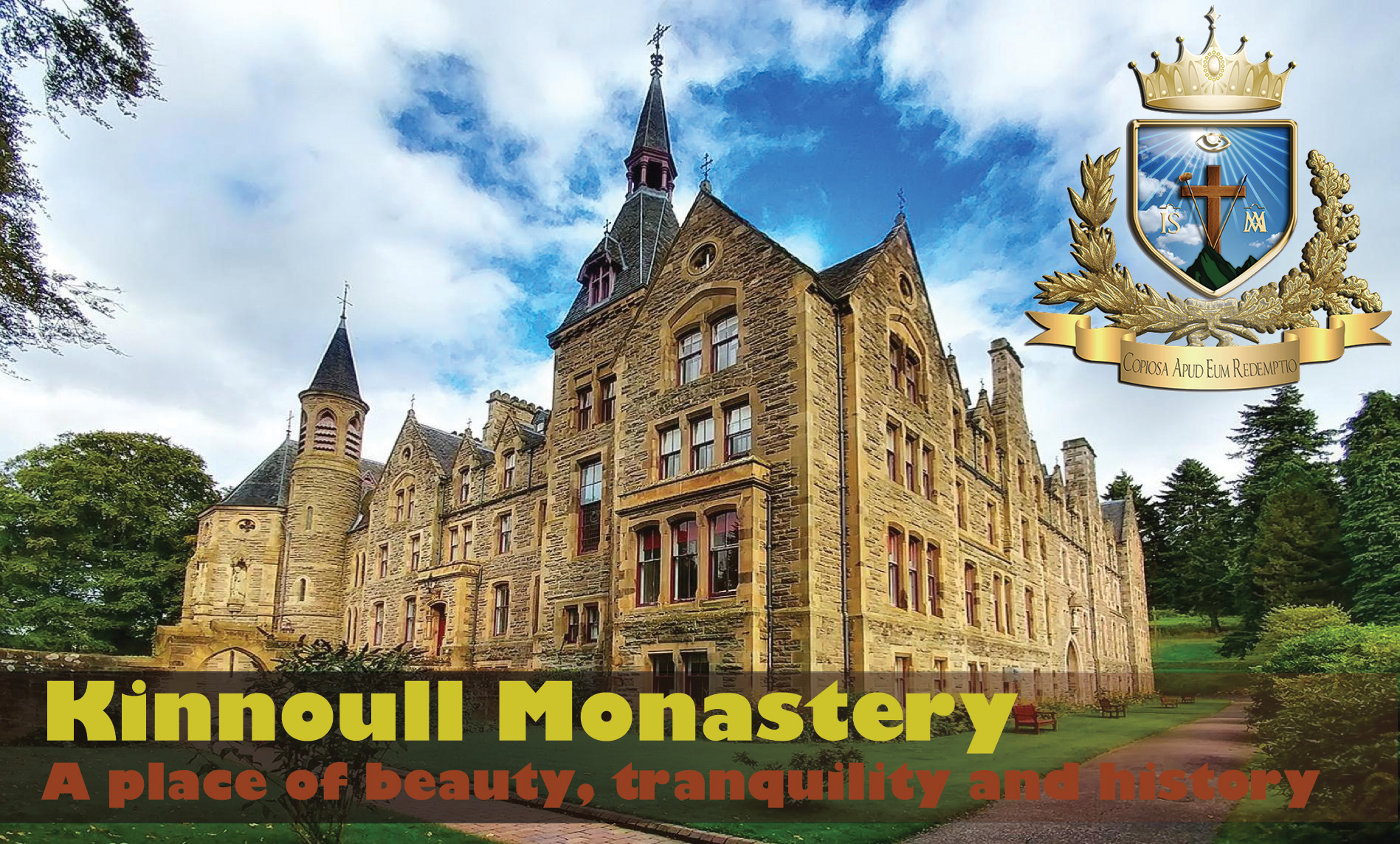

A member of the English Province, Fr. Douglas used his inheritance to retire the debt of the newly-built St. Mary’s Clapham and to establish the monastery at Kinnoull, Scotland in 1867. He also allotted a thousand pounds towards the establishment of the Irish Foundation in Limerick in 1853. Based on three opinions, the family fortune was believed to be derived from the income of Haig and Haig, the Scotch whisky distillery.

On March 23, 1898, Fr. Douglas died of the flu at the age of 78 and was buried in the crypt of the Casa S Alfonso house chapel along aside the Superiors General.